The Road Taken: Patriotism, Teamwork, Challenge

By Rudi Williams American Forces Press Service

WASHINGTON -- Bill Woods dropped out of high school at 17 to join the Army on Sept. 24, 1947, intending to serve three years, get out of the Army and use the GI Bill to pursue a college education. But patriotism got in the way.

As planned, Woods got out of the Army on June 20, 1950, and started his quest for a college degree. "But shortly after I got out the Korean War broke out," said Woods, who had served in Korea before the war and spoke some Korean and Japanese. "I'd already signed up for courses when I learned my old unit was one of the first committed to the war zone.

"I became heartsick about not being with them," the 69-year-old retired Army master sergeant said. "I got all upset and re-enlisted in February 1951."

He was hoping to hook up with his old unit – Company A, 21st Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division. Instead he was assigned to the 48th Field Artillery Battalion, 7th Infantry Division.

"I was happy not to be in the infantry," said the Cambridge, Mass., native. But, as he sees it now, he might as well have been. That's because the morning after returning to active duty, he was issued a 42-pound radio, two extra batteries, an M-1 rifle, 120 rounds of ammunition and his rucksack. His destination: an infantry outfit on an artillery forward observation team.

OPERATION RIPPER

U.S. military leaders launched Operation Ripper on March 7, 1951, to drive enemy forces out of Hongch'on and Ch'unch'on and to reach "Idaho," a line drawn just below the 38th parallel in South Korea.

In the process, they hoped to destroy significant numbers of enemy troops and their equipment while splitting Chinese and North Korean forces.

Operation Ripper was preceded by the largest artillery bombardments of the Korean War. U.N. forces moved into Seoul on the night of March 14, marking the fourth time the capital had changed hands since June 1950. The South Korean flag was raised on the heavily damaged city, then home to about 200,000 of its prewar population of 1.5 million people.

The enemy retreated north. U.N. troops ground forward, constantly descending sharp slopes or climbing steep heights to attack enemy positions that were sometimes above the clouds. Each enemy strongpoint had to be captured by infantry assault. By the last of March, U.S. forces reached the 38th parallel.

vWoods said he became so good at helping to direct artillery he advanced from private to sergeant in short order. But he said, "It was an awesome experience."

He survived the war unscathed, "but I got the hell scared out of me a few times with artillery shells and mortars dropping in close." He remembers being knocked to the ground by "something." "It was like a jet plane going across the back of my head," Woods recalled. "I was on the ground for two or three minutes before finding out what it was -- a Chinese recoilless rifle shell. It couldn't have missed my head by more than a foot. I don't know how it missed me. I was never so stunned in my life."

Two winters of bone-chilling Korean weather are among the worse things that happened to him during the war, Woods said. "Korea has to be one of the coldest places on Earth," he said.

Returning home in March 1952, Woods became an instructor at the radio operator's course at Fort Dix, N.J. After a few months, he was off to Korea again, but then diverted to work with the Japanese self-defense forces.

Thoughts of getting out of the Army surfaced again in 1954. "But then, I weighed the options: I already had six years active duty. If I served 14 more years I'd have a guaranteed retirement check for the rest of my life."

So he re-enlisted and served a 1955-56 tour in Germany before returning to Korea for the third time in 1958 to serve with the 1st Cavalry Division. He returned to the United States in 1959, but was back with the division on the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea in 1961 -- his fourth tour in Korea.

In November 1964, Woods volunteered for Vietnam and served with the 114th Aviation Company (Air Assault). Four months later, he was assigned to battalion communications sergeant in a transfer to the 13th Aviation Battalion.

He returned home in December 1965, but was back in Vietnam three years later. Landing during the 1968 Tet Offensive, Woods was assigned as an adviser to South Vietnamese army radiomen.

He extended in Vietnam until April 1970 "because I wanted to see this thing through until we won it," said Woods, who wears two Bronze Star Medals, an Air Medal and 10 battle stars, three from the Korean War and seven from Vietnam. "When I left, I could go all the way to the Cambodian border without being attacked. Then everything changed."

Lady Luck was with him again. He left Vietnam without a scratch. "I took some chances and had some close calls, but I was never wounded," he noted. "One time a jeep behind me was blown up by a land mine in an area I'd just walked through."

Woods said he volunteered for combat so many times "because that's what I was in the service for. It bored the hell out of me to sit back in the United States giving classes, working on a set schedule and making formations.

"What the hell are we in the service for if we can't get there and use what we're taught?" Woods said. "It's the job and, I'd much rather get out and prove myself. Today, it would be the same thing if I had the opportunity. In fact, I was a little disappointed that they didn't call me up for the Persian Gulf War."

After retiring June 1, 1970, Woods worked as a driver and as bodyguard for the chairman of the board of a major corporation. He later bought a dry cleaning business and he ran it for nine years. After that, he was a bartender and manager of a lounge in Somerville, Mass., for five years.

"It was a 'Cheers' type of place and I really enjoyed it," Woods said. "It was the best job of my life." Problems with his right leg ended his fun bartending career.

Fearful of losing his leg, Woods drove to Washington to consult physicians at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. The Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home nearby was the most economical lodging he could find.

"I fell in love with this place," said Woods, who became a resident in March 1993. Moving in created another fear: being retired with no job and nothing to do.

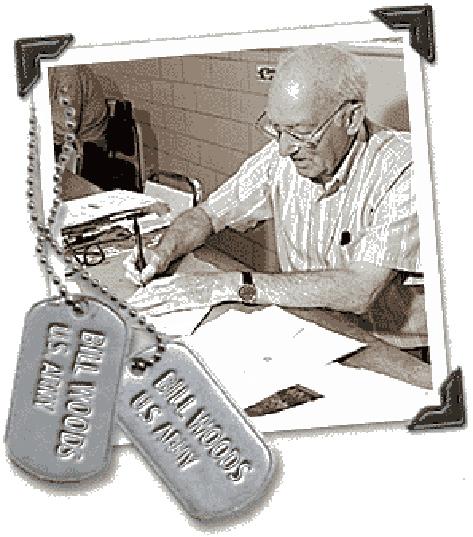

The White House came to his rescue. It sent out a cry for help to deal with mountains of mail it was receiving after President Clinton took office. Woods joined the retirement home mail detail that was bused to the White House every Thursday. The home opened a White House mailroom annex awhile back and Woods still volunteers there 20 hours a week and spends another 20 in the home's public affairs office.

"I'm 69 now, and as long as I can still be productive I'm happy," he said. "When you're no longer as useful as you'd like to be, this is a good place to be. You can always find something to do. They treat you well and with respect."

- Log in to post comments