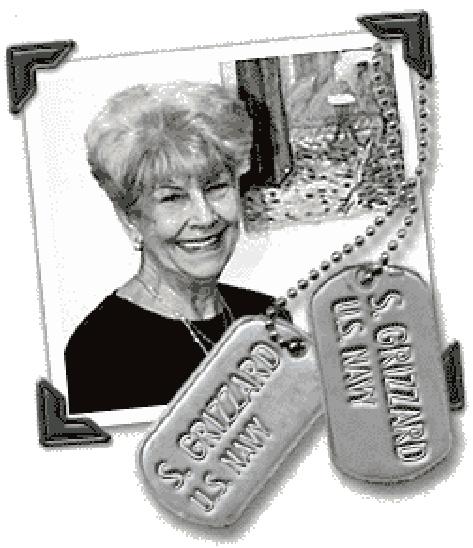

Queen of the Ball Treasures Naval Service

By Rudi Williams American Forces Press Service

GULFPORT, Miss., March 22, 2000 -- Suzanne M. Grizzard told "a little white lie" to get into the Navy in November 1943. She was only 18 years old but told recruiters she was 20 -- the required age for women to join in those days.

"I come from a seafaring family; why do you think I joined the Navy," Grizzard said good-humoredly. Her daddy, a Merchant Marine captain, was proud she joined, but her mother thought it was "terrible."

"My mother thought the Navy would teach me to drink, smoke and chase sailors; and it did," the 74-year-old Naval Home resident said with a throaty laugh as she blew cigarette smoke into the air.

Born on Jan. 25, 1926, in Mobile, Ala., Grizzard, was the youngest of four sisters and three brothers. During World War II, her father, Merchant Marine Capt. Chamberlin Berke Foster, was given an honorary commission as vice commodore of the commercial fleet of merchant ships during the Normandy Invasion. Her late oldest brother, Carey B. Foster, was a Gulf Oil tanker captain. Her brother, Burns Foster, was head of the Maritime commission in New Orleans. Her mother was a housewife.

"My father went ashore after the D-Day invasion," Grizzard noted. "I used to have all his water proof maps – big maps -- but they were lost in storage.

"My daddy brought back one little bush of pink roses from the Normandy beach and called it his Normandy rose," she said. "I planted it at my house in Pensacola (Fla.) and it grew to be a huge bush about four feet tall. He said it looked so lonely sitting on the beach by itself and he couldn’t resist it."

Naval Women in World War II President Franklin D. Roosevelt changed the course of naval history July 31, 1942, when he created the WAVES -- Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service by signing an amendment to the Naval Reserve Act of 1938.

WAVES filled shore billets in communications, intelligence, supply, medicine and administration, thereby freeing male sailors to fight during World War II. When the war ended in l945, more than 84,000 commissioned and enlisted WAVES were on duty, with 8,000 more in training. This was in addition to more than ll,000 Navy Nurse Corps officers, ll,000 Coast Guard SPARS (named after the service's motto "Semper Paratus," "Always Ready") and some l8,000 women Marines.

The Coast Guard women were assigned stateside as storekeepers, photographers, pharmacist's mates, cooks, and numerous other jobs.

Commissioned officers were limited to one lieutenant commander, and up to 35 lieutenants and 35 lieutenants junior grade.

Navy nurses served stateside, overseas on hospital ships and as flight nurses during the war. The Japanese captured five Navy nurses on Guam and held them as POWs for five months before exchanging them; they held 11 captured in the Philippines for 27 months.

Grizzard calls her "little white lie" about her age to get into the Navy a "patriotic lie." That's because, she said, "When they bombed Pearl Harbor I was very excited and wanted to do something to help with the war effort. I worked at the ration board until I felt I could go into the service."

Gizzard really wanted to go overseas, but was never ordered to do so.

While in boot camp at Hunter College in New York City, she took an aptitude test hoping to qualify as a Link Flight Trainer operator. But instead, the Navy sent her to a nurse cadet school at Bethesda, Md.

"It was a nursing training crash course so you could relieve the nurses to go overseas," Grizzard noted. "It was four grueling months, eight hours a day, plus your chores. I only had two liberties in four months. It was really tough, plus all the other chores I had to do –- squeegeeing the floors, washing windows – Navy stuff. I couldn’t fail, otherwise I’d be out of the service."

Grizzard is still incensed about not getting the rank she thinks she deserved. "For some reason, they stopped the program and I was caught in the crack," she said.

"I’m still upset about what they did to me at Bethesda," she said. "Most corpsmen when to school for only six to eight weeks and I went four grueling months and they didn’t do me right. I only got one stripe and that wasn’t fair. I knew more than a corpsman. That was the unfair part of my service life."

Aside from that, she said her Navy experiences were all "pleasurable to me because I like people. I like taking care of them and I learned a heck of a lot. You can’t be dumb in the service and make a lot of mistakes."

In late 1945, the Navy discovered her true age and discharged her. "I got out for a short period and joined the Naval Reserves for about two months, then went right back in when I became of age," Grizzard said with a hearty laugh.

Her first duty station was the Philadelphia Naval Hospital working with amputees and the blind. She later served at naval medical facilities in New Orleans and Memphis, Tenn., before getting out for good in 1950 as a hospital corpsman first class.

In 1949 she met a Marine from her hometown. "The Navy didn’t tolerate pregnant women back then," said Grizzard. "I’d done my job well and had graduated from operating room technician school in Pensacola, Fla. I was the only woman in the class with nine men."

The Marine she met and married was Master Gunnery Sgt. James E. Pryor who was a gunner in the Army Air Corps before switching to the Marines. The couple had four children: James Pryor Jr (1951), Edwin Pryor (1953), Dolle (1956) and Jamie (1955). James Jr., spent three years in the Marines. She has three grandchildren.

Grizzard is still struggling with dealing with the murder of her daughter Jamie three years ago.

Her first marriage ended in 1979. She married her second husband, who was 20 years younger than she, about a year later. But she still has warm feelings for her first husband "because he is the father of my four children," Grizzard said. "He had more damn ribbons that I’ve ever seen on anybody -- the French Croix de Guerre with Palm, two Silver Stars, Bronze Star, the Navy-Marine Corps Medal and a bunch of other stuff I don’t remember," she said.

When Grizzard got out of the Navy she went into pre-med at the University of Alabama. She said her Navy medical training paid off in civilian life. "Because of my training, I was able to find work in hospitals and for physicians in private practice as an operating room scrub nurse," she said. But she was forced to change fields when she suffered a hearing loss and had an operation on her ear.

"I couldn’t hear well enough to continue working in the operating room, so I obtained a job in the Jackson County Court House Mississippi as a personal property tax assessor," Grizzard said "I worked there nearly six years and retired when I was 62 because I got tired."

She owned a shop in Mobile where she sold some of her paintings and her sister's ceramics.

Grizzard said the most interesting part of her life was when her first husband left a management job with H&R Block in Atlanta and established 12 tax offices of his own. "He made beaucoup money; that man could make money," said Grizzard, who stayed home and started painting. "He ran for sheriff in Fulton County, Ga., and won the preliminary. That was a swinging town. My husband was president of the Young Republican Voters League and I was the secretary.

"I met Richard Nixon – good-looking sucker he was," Grizzard said with a laugh. "We associated with the governor, other politicians and the elite of Atlanta and Georgia. I was the queen in one fourth of July parade and the next year, I rode on the Republican Party float with cowboy actor James Brown and Victor Jory was the grand marshal.

"I was the queen of the ball, but I was also very young – kind of a hippie," she said. "I’m not queen of anything here. There’s nothing to be queen of here."

- Log in to post comments