Former Pug 'Kid Odell' Reflects On Navy Career

By Rudi Williams American Forces Press Service

WASHINGTON, April X, 2000 -- Former boxer and trainer Odell Williams was a realistic young man. "Kid Odell" knew he would never win many bouts, much less be a contender for the welterweight title.

Other than the fight game, "Kid Odell" said he was like a lot of young people in Depression-era 1936, "just out there not knowing what to do with themselves." He made his amateur boxing debut at 14 and had won only nine professional fights when he quit at age 23.

"I tried hard, but I wasn’t good enough," said Williams, an 87-year-old resident of the Naval Home in Gulfport, Miss. "I joined the Navy after I discovered I’d just be an average fighter, maybe end up being punch drunk." He opted for another living -- in the U.S. Navy.

Williams became interested in becoming a sailor at an exposition in San Diego when he saw three petty officers, two African Americans and one white, decked out in crisp Navy uniforms with gold chevrons, "hash marks" and buttons. He was mesmerized by their appearance and wanted to be just like them.

"I asked them about the Navy, and they said, 'You can't get into the Navy now; you can't be like us," Williams said. But he was so intrigued by them that he ignored their discouraging comments and started searching for ways to get into the Navy. The young pugilist didn't understand racism -- he'd grown up in a Los Angeles neighborhood where his was one of only two African American families, but everybody got along well and looked out for each other.

"Everybody went to school and played together -- Italian, Jewish, whites and blacks," he noted. "If you were out on the streets after nine o’clock, an adult would want to know why you were out there that time of night."

Williams was told the Navy only accepted African Americans for its steward service. That didn’t deter him. He joined the Navy on May_7, 1936, as one of 12 African Americans from the Los Angeles area selected for an integrated boot camp training program.

Navy Ships Named in Honor of African Americans

WASHINGTON, May 1, 2000 -- It took more than 168 years after the Continental Congress authorized the first ship of a new Navy for the United Colonies on Oct. 13, 1775, before a ship was named for an African American.

The first ships were named after kings (Alfred the Great), patriots (John Hancock), heroes (USS Nathanael Greene), ideals (USS Constitution), institutions (USS Congress), American places (USS Virginia), and small creatures with a potent sting such as Hornet, Wasp.

The first ship named in honor of an African American was the USS Harmon (DE-678), a 1,400-ton destroyer escort, commissioned in August 1943. It was named in honor of Mess Attendant First Class Leonard Roy Harmon, who posthumously was awarded the Navy Cross for heroism during the Battle of Guadalcanal on Nov. 13, 1942. He was killed in action aboard the cruiser the USS San Francisco.

Nine other Navy ships have been named in honor of African Americans. Two are under construction.

The nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine USS George Washington Carver (SSBN-656) was the next craft named in honor of an African American. The submarine honors scientist George Washington Carver (1864-1943). Commissioned in June 1966, the Carver carried out 73 patrols in the Atlantic area until mid-1991. She was decommissioned in March 1993.

The USS Jesse L. Brown (DE-1089 and later FF-1089 and FFT- 1089) was named in honor of Ensign Jesse L. Brown, USN (1926-1950). Brown was the first African-American naval aviator, and was killed in action during the Korean War.

The USS Miller (DE-1091, later FF-1091) was named in honor of Cook Third Class Doris ("Dorie") Miller. Miller was awarded the Navy Cross for heroism during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. The Miller was commissioned in June 1973 and was transferred to the Naval Reserve Force in January 1982. She was decommissioned in October 1991.

The USNS (U.S. Naval Ship) Pfc. James Anderson Jr. (T-AK- 3002) was named in honor of Marine Pfc. James Anderson Jr., who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism during the Vietnam War. A maritime preprositioning ship, the Anderson was built in Denmark in 1979 as the merchant ship Emma Maersk. She's based at Diego Garcia, an island in the Indian Ocean, and carries equipment to support a Marine expeditionary brigade.

The guided-missile frigate USS Rodney M. Davis (FFG-60) was named in honor of Marine Sgt. Rodney M. Davis, who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism during the Vietnam War.

The USNS Henson (T-AGS-63) was named in honor of the Arctic Explorer Matthew Alexander Henson (1866-1955) who accompanied Robert E. Peary when he was credited with discovering the North Pole in 1909. The Henson was commissioned in1998.

The USNS Watson was named in honor of Army Pvt. George Watson, who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism during World War II.

The USS Oscar Austin was named in honor of Marine Pfc. Oscar P. Austin, who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism during the Vietnam War. The Austin is an Arleigh Burke class guided missile destroyer. The Austin is under construction and is scheduled for commissioning in August 2000.

A 10th ship honoring an African-American Navy Cross recipient, Navy Cook 3rd Class William Pinckney, is under construction. No commissioning date has been set for the Pinckney (DDG-91). The ship is named to honor Pinckney's heroism aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise during the Battle of Santa Cruz in 1942. He survived the battle and died in 1975.

"It was an experiment, trying to get blacks back into Navy jobs other than servitude positions -- cooks, stewards and shining officers' shoes and brass," he said. "A lot of people were not aware of this because the Navy was very secretive about it. It was too explosive to go public at the time."

Williams’ bout with integration in the Navy was short-lived. After boot camp, he and the other African Americans went aboard the battleship USS Texas and headed for Unit K-West U.S. Naval Training Station, Naval Operating Base, Norfolk, Va. -- for training as cooks and stewards.

"That’s when we were introduced to segregation," Williams said. Before retiring with more than 20 years' service, Williams served with Fighting Squadron Six aboard the carrier USS Enterprise; the oiler USS Salamonie; general stores issue ship USS Acubens; the former ocean liner President Jefferson, renamed the attack transport USS Henry T. Allen; attack transport USS Noble; cruiser USS Des Moines; and at Naval Operating Base Argentia, Newfoundland, Canada.

A world war and a manpower shortage during World War II forced the Navy to change it ways and accept African Americans in general service, the Marine Corps and Coast Guard on April 7, 1942. Williams credits President and Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt and educator Mary McLeod Bethune with spearheading the changes.

During World War II, Williams was a steward aboard the USS Enterprise, which he calls one of the greatest ships in the Navy at that time. When fighting erupted, he said, his battle station was "pyrotechnic engineer" -- "fuzing bombs and making smoke."

"The only other thing I did was work as a storekeeper," he said. "They forgot about you being a steward in those days." The only thing that mattered, he said, was whether you could do the job -- whatever was needed at the time.

Williams still treasures his service aboard the Enterprise as his best career memories. "I’ll never forget how the guys cooperated -- no color line or any of that stuff," he said. "You went to your battle station, no matter what your special duties were. Discipline was hard."

He said he’ll also never forget what happened when he went aboard the heavy cruiser USS Des Moines in 1950 as a young chief petty officer. That’s a bad memory.

When he reported aboard, his belongings were supposed to be taken to the chief’s quarters, but he found them in a passageway. Williams rushed back to the quarterdeck and asked the messenger, "Sailor, where did you put my gear?"

"In the chief’s quarters," the messenger answered.

Bypassing the officer of the deck, Williams complained to the executive officer, who told him, "We’re not having any trouble on this ship, so we’re going to give you a billet in officer’s country."

"I told him, 'I’m not an officer,' and asked to see the commanding officer," Williams said. "The captain called all the chiefs together and asked, 'Who set Chief Williams’ gear out in the passageway?'

"A chief bosun's mate from South Carolina yelled, 'I did, cap'n. I haven’t slept with them all these years and I’m not going to sleep with them now.'

"No one else said anything," Williams recalled. "The captain told the chief, ‘You take your gear and go down to the first class quarters.’"

Later, the chief made the mistake of picking a fight with the former pugilist.

"I did a pretty good job on him," Williams said. "He told everybody he fell down a hatch. About a month later, he came to talk to me and turned out to be my best friend. He said he thought all black people didn’t do a damn thing in South Carolina but get drunk on Saturdays. That was the impression he had of me.

"Not all of the white people were bad. There were a lot of good people in the Navy, but a lot of them wanted to hold that tradition they had years ago -- whites only," he said.

"My father-in-law was Caucasian and his grandfather owned slaves in Georgia," said Williams, who hasn't seen his wife for nearly 20 years and doesn’t have any children. "He treated me better than my own father. Sometimes you meet good people, no matter what their background."

Williams said he was involved in many battles, including the Battle of Midway aboard the Enterprise, but the only time he was wounded was when enemy rounds slammed into the USS Salamonie. He suffered shrapnel wounds, but refused treatment because "there were people laying on the deck."

"I didn’t get a Purple Heart because I didn’t ask for one -- the medal didn’t matter to me," he noted.

Williams is incensed about the way World War II veterans were treated. He doesn’t think they've ever received the credit they deserve.

"It bothers me to hear people going ape about the Korean War, Vietnam War and Desert Storm," he said. "If it hadn’t been for the guys in World War II, they wouldn’t have been around for Korea, Vietnam or Desert Storm. We made it possible for them.

"Why are they just beginning to recognize the guys who fought in World War II?" he asked. "Hell, most of them are dead. I’m 87 years old. I don’t need their help anymore."

In nearly the same breath, Williams said, "This country has its drawbacks, but it’s the greatest country in the world."

After retiring from the Navy in January 1956, Williams spent about five years in special security for the Los Angeles Water and Power Department before getting into the entertainment business as a master of ceremonies, singer and piano player.

Years later, he got into trouble with the Internal Revenue Service and decided to seek shelter at the Naval Home. One of the first questions he asked when he inquired about his eligibility was: "Is the home segregated?"

"No, it isn’t," the woman on the telephone answered.

"How many nonwhites do you have living there?" Williams asked.

"Four," the woman said.

Williams could hardly believe that. He accepted the woman's invitation to visit and assess the home in person. He liked what he saw and became a resident in August 1993. Even today, only five of the more than 440 residents of the home are African American.

Though retirees from all services are eligible to live at the home, the residents are mostly sailors and Marines, Williams noted. For that reason, he surmises that most of the residents are from World War II and the Korean War, and there weren't many blacks in the Navy in those days.

He also said speculated that many African Americans might not want to live in Mississippi, but he said major changes in race relations have occurred there in past years. For example, Williams takes pride in being invited to schools to talk to students about his military and life experiences. He's particularly proud because the majority of the students he speaks to are white, and he treasures the many letters of thanks they write to him.

He said he's proud because, "Back then, it was unheard of for a black man to go into a school and talk to white kids.

"When I’m invited to talk to kids, I stress discipline and ask them to define it for me to get them involved," Williams said. "I talk about self-esteem and tell them if you don’t think something of yourself, who is going to think anything of you? I talk about objectives, cooperation and how to get along with people and be responsible. And I tell them they should respect others as you respect yourself and forget racism. And forget peer pressure; if you have an idea, speak up about it."He tells the kids and anybody else who will listen: "The Navy and I grew up together and learned to respect each other."

His impression of living at the retirement home is: "This is like heaven for me," Williams said.

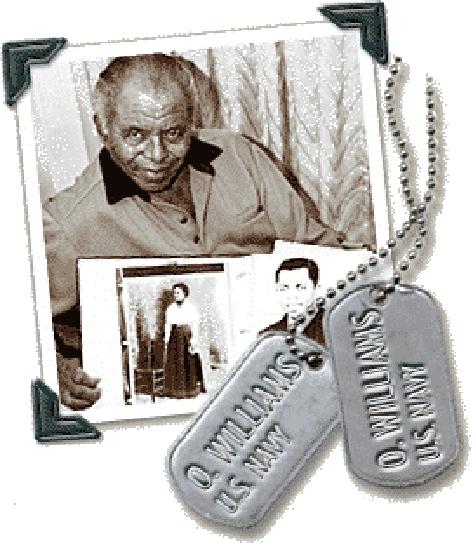

1odell williams Former boxer and retired Navy Chief Petty Officer Odell "Kid Odell" Williams shows off some of the photographic memories he keeps in his room at the Naval Home in Gulfport, Miss. Photo by Rudi Williams.

- Log in to post comments