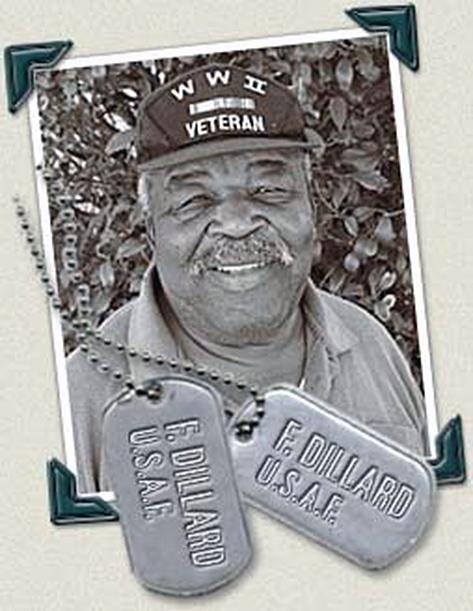

Air Force Sergeant Finds Happiness at Naval Home

By Rudi Williams - American Forces Press Service

As a young man, Frank Dillard, 75, was sweltering in the Alabama sun laying roadbed and railroad tracks while most of his friends escaped to the armed forces.

Dillard got smart on Oct. 11, 1946. "That's the day I joined the Army at the age of 21 -- out of patriotism, too," he said. "Putting in rails was heavy duty work. I was making 57 cents an hour, or $4.56 per eight-hour day, or $22.80 for a five-day week. The Army paid about $50 a month and gave you three meals a day and a place to sleep. I got away from that railroad."

His stint in the Army didn't last long. The 1942 graduate of Montgomery's all-black Booker T. Washington High School didn't say why, but he left active duty in 1948, joined the Army Reserve and went back to work for the railroad.

"I discovered that working on the railroad wasn't for me anymore, so I joined the Air Force," said Dillard. He trained in aircraft maintenance. He had been a heavy equipment operator in the Army.

He volunteered for the Korean War, but was turned down. "I was in Alaska for most of the Korean War," said Dillard, who also served in Germany, Japan, the Philippines, Guam and Hawaii. "The older guys volunteered to go overseas so they'd quit killing all those young boys, but they told us they needed the seasoned men back here."

He served in an aircraft refueling outfit in Alaska from 1949 to 1951. After a one-year assignment in one of the "lower 48," he returned to the Alaska unit to serve from 1952 to 1954.

Dillard also served with the 7030th Materiel Squadron, a U.S. Air Forces in Europe outfit; the 1600th Maintenance Squadron, 1600th Maintenance and Support Group at Westover Air Force Base, Mass.; the Army's 9206th Station Complement Technical Service Unit at Camp Stoneman, Calif.; and a Strategic Air Command maintenance unit at Pease Air Force Base, N.H.

When he retired from the Air Force on Sept. 30, 1968, he used his Army training in heavy construction to get a job. He then obtained a job as a supervisor on roads construction projects and later moved to sewage treatment plants and nuclear power plants in Portsmouth, N.H.

"The nuclear power plants closed in 1984. I went back home to Montgomery in 1985 and bought a house near my brother's house," he said. "I worked as a bricklayer with my nephews, who are general contractors."

Dillard said his last brother died in 1998. "That just tore me up -- sent me over the creek," he said. "That's why I'm here (at the Naval Home). He was 70 years old, but he was my baby brother."

Dillard's father died more than 60 years ago, and his mother passed in 1967. His other two brothers and sister died years ago. "I'm the last one of that generation of my family, but I have four nephews and a bunch of cousins."

In his view, he has sound advice for retirees who are still paying for their homes: "Get rid of it." He said before becoming a Naval Home resident on Oct. 13, 1998, his home in Montgomery, "was running me crazy. Here, I don't have to worry about painting or fixing this or that and all the other things you have to do when you own a home."

Dillard said living in the Naval Home was the last thing he wanted to do, but it's grown on him.

"It's a beautiful place," he said. "Before I got here, I thought I'd be more comfortable at the Soldiers' and Airmen's Home in Washington, D.C., because I don't know much about the state of Mississippi." The Washington home, however, had no vacancies.

Dillard said he wasn't surprised to learn on his arrival that only four African Americans lived at the Naval Home. He noted that most of the home's 450 residents are retired Navy people from the World War II and the Korean War years.

"In those days, there were not many blacks in the Navy," he said. But he also surmised that many African Americans don't know about the Gulfport home.

"Or, like me, they feel they'd be more comfortable in Washington, D.C.," Dillard said. "I found out about this place from the people in Washington. They suggested that I apply here because it would take about a year before I'd be considered there. I was accepted here in 60 days."

"The people here are nice and they treat you well, but you pay for what you get," he said. "You pay 40 percent of your income to live here."

However, he credits being at the home with improving his health. "My diabetes and high blood pressure have gotten better since I came here," Dillard noted. "I've gotten good medical care here. But dental care isn't free. Your insurance pays a lot of money for dental care here."

Residents can also use the Veterans Affairs Hospital, which is close by.

"I'm happy to be here now," Dillard said, "but when I think about my time in the Air Force of the late '40s, '50s and '60s -- I went through hell.

"The Air Force didn't 'go' equal opportunity until 1968, after I got out," he said. "A Negro didn't make any stripes in the Air Force before that. It was tough on a black man."

With some bitterness he recalled an experience in 1963 when he was "hand-picked to straighten out a motor pool in Germany that had failed several Air Force inspections." He straightened it out, he said, and the motor pool passed the next inspection.

"Who got the promotion? The white guy who was there when they kept failing. He was my supervisor," Dillard said. "After they gave him credit for what I did, I wrote a letter to the general and he got me out of there. I've always been the man to go straighten out something and somebody else got the promotion.

"I'm out of it now, but when I look back, I just shake my head," he said. "I've always been vocal about racial things. I try not to look back at it because I don't want anything to bother me at my age."

- Log in to post comments