Pearl Harbor attacked: A witness remembers, 70 years later

By Sylvia Carignan, Published: December 6.

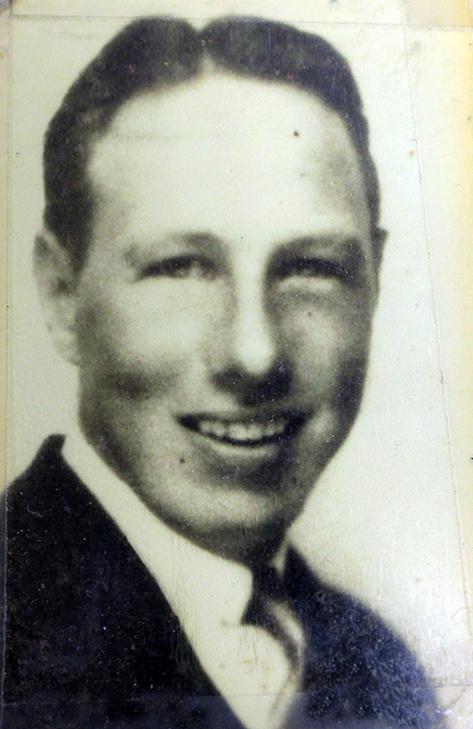

Around 8 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941, Army Private Francis Stueve sat down to breakfast with the rest of the 89th Field Artillery battalion, stationed at Pearl Harbor.

“As quiet a day as you’ve ever seen,” Stueve remembers now. “Beautiful sunshine, nothing going on.”

Suddenly, not far from his seat in the dining hall: bang, bang, bang.

“Somebody says, ‘It’s the Chinese New Year,’ ” he said.

But then, a bullet broke through the glass window of the dining hall. Another flew just past Stueve and knocked the butter dish off the table. Japan’s official declaration of war would come a day later, after the loss of 160 aircraft, 12 ships and 2,300 Americans, according to the Library of Congress — 70 years ago on Wednesday. Stueve, now 94, can describe his experience as if it were happening now:

Bewildered by the bullet, Stueve, then 24, and a few other men ran outside.

“We’re looking at the clouds, and watched a Japanese plane that had its signals on,” he said.

It was common for American planes to practice maneuvers, Stueve said, but he soon realized the Japanese plane was bent on attacking his base and his fellow soldiers. “We were getting shot like everything was going to be destroyed,” he said. Soldiers fell left and right, buildings were hit by gunfire and ships suffered fatal gashes. “We had so many casualties. It’s a hard thing to do when people are screaming for aid . . . and you don’t have nobody coming,” he said. “Some who were looking out for their own were also getting killed.” With the continental U.S. thousands of miles away, Stueve said they felt isolated on the Hawaiian islands, fighting back without aid or relief. The base at Pearl Harbor had about one-sixteenth of the equipment they would have needed to defend themselves, Stueve said.

But it could have been worse. Despite the destruction, Stueve said the Japanese underestimated their own power.

“If they would had known how much they damaged,” he said, “they could have taken the whole works. One regiment of troops.”

From the time of the attack to the long cleanup, Stueve said the most difficult part of his job was communicating with native Hawaiians, many of whom didn’t speak fluent English. “For me to explain to a bunch of people who didn’t speak English — to do this and that, help this and that,” he said. “I had to get somebody to work psychologically with the people there; otherwise it would never work out.” Stueve was initially trained as an infantryman, fighting the enemy on the ground. As he got to know the Hawaiian islands, he moved to an artillery assignment.

He eventually spent 20 years in the Army, and saw more than 500 battles. Stueve came home to rural Iowa find that his parents had passed away.

“I didn’t know where to go after that. I joined the Air Force, and they sent me to Iceland,” he said.

After spending time in Germany, he came back to Andrews Air Force Base, where he retired. He’s spent the last few decades at a veterans’ retirement home in Northeast D.C. Stueve said the home hasn’t gone out of its way to recognize the anniversary for the dwindling number of resident eyewitnesses. In years past, he said, they’ve done nothing. “Nothing! They say, ‘We’ll feed you dinner, set you at the table.’ Just like every other night,” he said, chuckling.

But this year is more significant. In the Armed Forces Retirement Home’s December newsletter is a listing for an observance of the 70th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. The date will be solemnly marked with a ceremony and lunch.

- Log in to post comments