By Rudi Williams - American Forces Press Service.

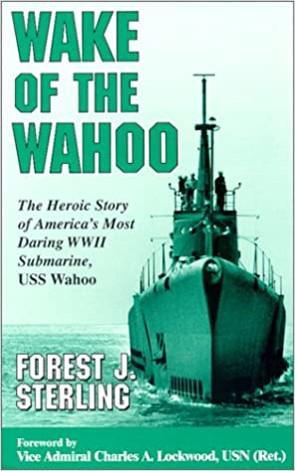

What happened to Forest J. Sterling on Sept. 13, 1943, was nothing short of a miracle. Sterling, who had survived five spine-tingling combat patrols aboard the submarine USS Wahoo, was set ashore on Midway Island to attend stenography school in the United States. About 45 minutes later, the Wahoo submerged on its seventh war patrol -- never to return. After more than 57 years, the 89-year-old resident of the Naval Home here said, "I can never understand why Capt. (Cmdr. Dudley W.) Morton changed his mind and transferred me at the last minute." He also made the comment in the epilogue of the third printing of his book, "Wake of the Wahoo," in July 1997. The fourth edition was printed in 1999. The heroics of the Wahoo's crew and commander are legendary and have been extolled in print and on the silver screen. "Most authors of submarine stories are officers, and they write on technical terms and about the heroics of officers," Sterling said during an interview in his room at the Naval Home. "I wrote of my experiences -- the experiences of enlisted men. One woman told me she was married to a submariner for nearly 20 years and she had to read my book to find out what went on aboard submarines. Submariners are notorious for not talking about what they do."

Naval History Immortalizes 'Mushmouth' Morton, USS Wahoo. The World War II "hero" submarine, USS Wahoo, was among 52 American submarines that made the supreme sacrifice during World War II. But before the Wahoo went to a watery grave, the sub and its skipper, Cmdr. Dudley W. "Mushmouth" Morton, racked up an extraordinary combat record. In his book, "Wake of the Wahoo," the sub's chief yeoman, retired Navy Chief Petty Officer Forest J. Sterling, said Wahoo flew a string of more than 20 miniature Japanese flags, symbolizing the number of enemy vessels she'd sunk. Sterling called Morton "a natural leader and born daredevil" and "an uncommonly talented submarine officer." Morton was endeared by his Naval Academy (Annapolis, Md.) classmates as "Mushmouth" because of his knack for yarn-spinning. In Morton's 10 months of command, Wahoo's impressive "firsts" included being the first sub to successfully attack an oncoming enemy destroyer using the "down-the-throat" shot and first to wipe out an entire convoy single-handedly. Another "first" possibly propelled "Mushmouth's" executive officer, then Lt. Cmdr. Richard H. "Dick" O'Kane, into "daredevil" status, too. Naval Historical Center researchers at the Washington (D.C.) Navy Yard said the most extraordinary of Morton's many innovations aboard the Wahoo was having O'Kane man the periscope. O'Kane earned three Silver Star medals for valor aboard the Wahoo and left after its fifth patrol to skipper the USS Tang. He went on to sink 31 ships, more than any other U.S. sub, and to earn the Medal of Honor and retire as a rear admiral. "Postwar examination of enemy records reveals a report that, on Oct. 11, 1943, in La Perouse Strait, 'Our plane found a floating sub and attacked it with three depth charges.' That may be the epitaph of the Wahoo and 80 American fighting men," retired Navy Vice Adm. Charles A. Lockwood wrote in the foreword to Sterling's book, first published about 15 years after the war. The Oct. 18, 1943, edition of "Time" magazine glorified Wahoo's last patrol as achieving "one of World War II's most daring submarine penetrations of enemy waters, a feat ranking with German Gunther Prien's entry at Scapa Flow, the Japanese invasion of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. raid in Tokyo Bay." When the "daredevil skipper" died, his claimed sinkings exceeded those of any other U.S. sub commander: 17 ships for 100,000 tons. A postwar accounting readjusted this tally to 19 ships and 55,000 tons. In terms of individual ships sunk, Morton was one of the top three U.S. sub skippers of the war, according to Naval Historical Center researchers. "Mushmouth" and the Wahoo became legends. "Mush" received three Navy Crosses in his lifetime and a fourth posthumously "for extraordinary heroism and outstanding course as commanding officer of the USS Wahoo during action against enemy Japanese forces…." He also held the Army Distinguished Service Cross.

Wahoo, named after a dark blue Caribbean food fish, earned six battle stars for World War II service. [Related Site of Interest: America's Submarine Centennial: Celebrating 100 Years of U.S. Navy Submarines]

"Wake of the Wahoo" is packed with anecdotal examples of enlisted men's "jitters, courage and humor before and after an attack." In one anecdote, Sterling recalls leaning with his back against the forward bulkhead when he started wondering if a depth charge "transferring its shock wave through the hull of a submarine might not be powerful enough to break a man's back." He said the thought made him uneasy and he moved out to the end of the bench away from the partition. After lengthy bouts with procrastination, Sterling wrote "Wake of the Wahoo" 15 years after World War II to chronicle his experiences and those of his fellow enlisted submariners. He tasted the humor, concerns, anxiety, fear and heroics of sailors as the Wahoo's chief yeoman. A soft-spoken, good humored, quick-witted man, Sterling re-emphasized that he "was the last man transferred about 45 minutes before she sailed on her last patrol." "I thought I'd return to submarine duty after finishing stenography school in San Diego, but I was assigned to a transport ship, the USS Comet." He was aboard the Comet during the initial landings on Saipan, Tinian, Guam and Leyte before being returned to submarine duty at Pearl Harbor.

Reflecting on his trek into the Navy, the Trenton, Mo., native and son of a coal miner joined the Navy on his 19th birthday -- June 4, 1930. In a way, he said, he was tricked into enlisting by a high school buddy who backed out after getting to the Navy recruiting office. "I started as an apprentice seaman and I believe for the first four months you got $18 per month," Sterling said. "Then you automatically went to seaman second class and got about a $3 per month raise." After boot camp at San Diego, he spent a month studying to be a radio operator, then reported aboard the submarine tender USS Holland and went on maneuvers in Panama. After being promoted to radioman third class, Sterling went to China for three years with the Asiatic Fleet that spent six months in Tsingtao, China, in the summer, then six months in Manila, the Philippines. He got out after seven years and stayed out too long to get back in. In those days, Sterling said, he was a quiet, hard-working, hard-drinking kind of guy who earned a buck anyway he could -- washing dishes, selling newspapers, bookkeeping and stock-clerking in Fabens, Texas, near El Paso. "I worked hard, but I had a habit of going across the street and getting drunk on Saturday night," he said. "One Saturday night, I got challenged by the town bully and whipped him. When the office found out, they told me I had a future with them if I promised to quit drinking, but I couldn't promise them that." He took any job that paid a few bucks as he traveled across the country, finally ending up as a clerk-typist in Los Angeles. "It was in the middle of the Depression and my parents were divorced, so I didn't have a family to go to, so I just knocked around," Sterling said. Fed up with "knocking around" and getting into trouble, Sterling decided to take another stab at re-entering the Navy. The Navy was suffering from a shortage of manpower to help fight World War II and he was accepted back in 1942. He asked to be a yeoman, and the Navy gave him the job based on his civilian experience. Assigned to a Seabees unit in San Diego, Sterling signed up for submarine duty when the Navy asked for volunteers. "They sent me to Pearl Harbor, where I went aboard the USS Wahoo in August 1942," he noted. His skipper, Morton, set several records during the early part of the war. "We were the first submarine to do a lot of things, like going into an unknown harbor and sinking a Japanese destroyer," Sterling said. "We were the first submarine to sink an entire convoy of ships -- four ships." The Wahoo is listed among 52 American submarines lost in World War II. Japanese reports inspected after the war showed that the Wahoo apparently sank four ships after sneaking into Japan's Inland Sea and that a patrol aircraft sometime later had attacked a surfaced enemy sub in an area where only the Wahoo could have been. When the Navy said all qualified submariners would be sent back to submarine duty, Sterling was sent to Pearl Harbor to become a member of the USS Seal in 1944. "She'd already made 12 war patrols and wasn't due to go out again," he said. He spent the rest of the war in Hawaii practicing for air warfare. "Whenever they'd find us, they'd drop hand grenades and scare the hell out of us," Sterling said. When the Korean War broke out, he was a member of a secret teletype communications crew. "They had a plaque with a fire ax and a 45mm pistol over the machines that said, 'In case of an invasion, you're to destroy the decoding machine and commit suicide,'" he said with a laugh.

Sterling retired as a chief petty officer in August 1956 and worked for a while in San Diego with the state motor vehicle department and as a motel night clerk until he was eligible for Social Security. Meanwhile, he completed two years of English at Ventura (Calif.) College with thoughts of writing a book. He also attended submarine veterans meetings and took notes about their experiences. "I'd come home pretty well polluted," said Sterling, whose wife didn't drink. "And I'd say, 'I'm gonna to write a book! I'm gonna to write a book!' "One day my wife said, 'We're going up into the mountains and rent a cabin and you're going to write that book,' " Sterling said. "That's how I got started. He packed up his research material, including copies of sailing lists. "I knew all the guys on the lists," Sterling said. "Then I wrote the Navy for a brief history of the Wahoo, because all the ships we sank were in that information. It also told me when and where, because I didn't trust my memory. "I tell people I have a great memory, but I have a lot of trouble with my recall," Sterling said with a laugh. After his wife, Marie, died in 1989 at age 86, he applied for residency at the Naval Home and was accepted in 1991. The couple was childless, and Sterling is an only child. "She was my pre-war girlfriend," Sterling said. "When I arrived in San Francisco aboard the Wahoo from Australia in June 1943, I called her in Los Angeles, where she was a telephone operator. I asked her, 'How would you like to get married?' She said, 'I'll be up on the next plane.'" Sterling ended his epilogue in the 1999 edition of the "Wake of the Wahoo," with, "At midnight, Jan. 1, 2000, in keeping with my predictions to my Wahoo shipmates, I expect to hoist a few beers and say to them: 'Sorry, fellows, I should have been with you. I can never understand why Captain Morton changed his mind and transferred me at the last moment. My spirit has been with you all these years!" s set ashore on Midway Island to attend stenography school in the United States. About 45 minutes later, the Wahoo submerged on its seventh war patrol -- never to return. After more than 57 years, the 89-year-old resident of the Naval Home here said, "I can never understand why Capt. (Cmdr. Dudley W.) Morton changed his mind and transferred me at the last minute." He also made the comment in the epilogue of the third printing of his book, "Wake of the Wahoo," in July 1997. The fourth edition was printed in 1999. The heroics of the Wahoo's crew and commander are legendary and have been extolled in print and on the silver screen. "Most authors of submarine stories are officers, and they write on technical terms and about the heroics of officers," Sterling said during an interview in his room at the Naval Home. "I wrote of my experiences -- the experiences of enlisted men. One woman told me she was married to a submariner for nearly 20 years and she had to read my book to find out what went on aboard submarines. Submariners are notorious for not talking about what they do."

- Log in to post comments